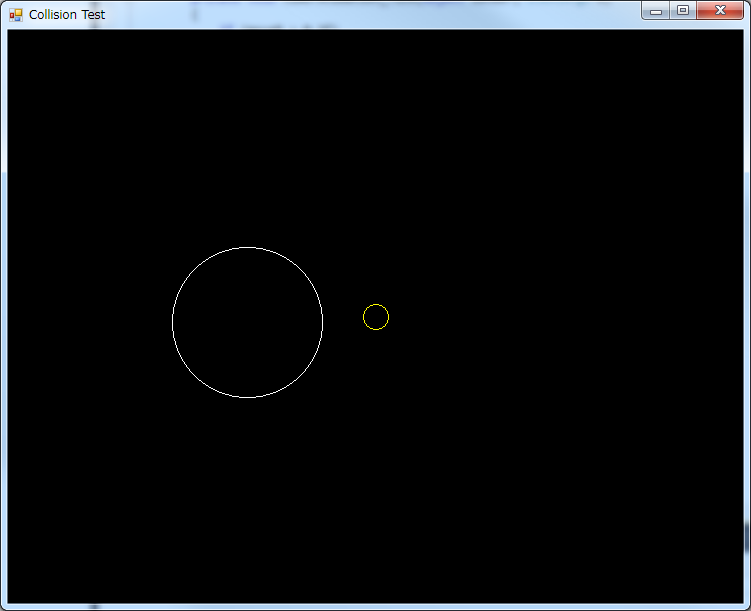

In our last article, we made a very simple program that helped us detect when two circles were colliding. However, 2D games are usually much more complex than just circles. I shall now introduce the next shape: the rectangle.

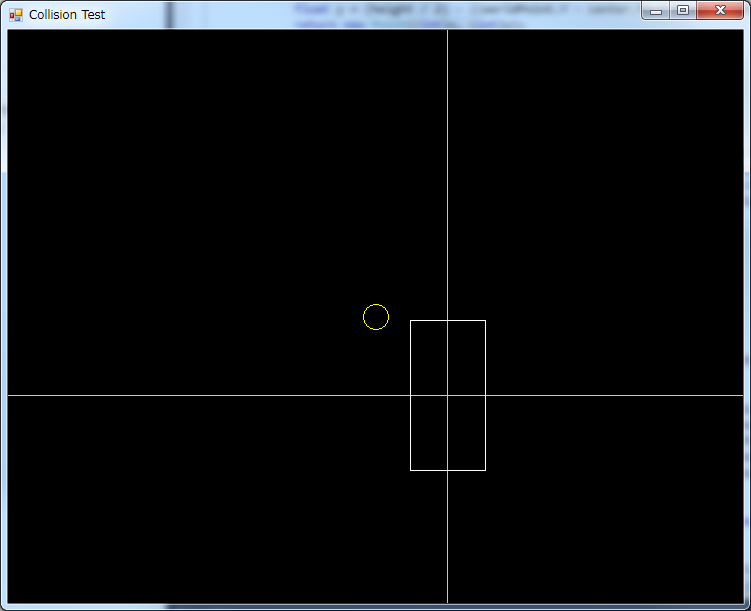

By now you probably noticed that, for the screenshots I’m using a program called “Collision Test”. This is a small tool I made to help me visualize all this stuff I’m talking about. I used this program to build the collision detection/resolution framework for an indie top-down adventure game I was involved in. I will be talking more about this tool in future articles.

Now, there are many ways to represent a rectangle. I will be representing them as five numbers: The center coordinates, width, height and the rotation angle:

public class CollisionRectangle

{

public float X { get; set; }

public float Y { get; set; }

public float Width { get; set; }

public float Height { get; set; }

public float Rotation { get; set; }

public CollisionRectangle(float x, float y, float width, float height, float rotation)

{

X = x;

Y = y;

Width = width;

Height = height;

Rotation = rotation

}

}

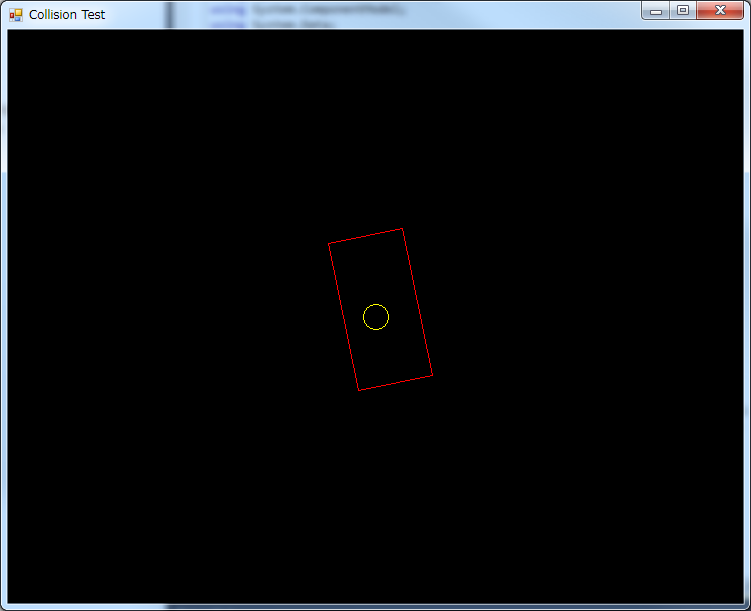

Now, for our first collision, we will collide a circle and a rectangle. There are two types of collisions to consider: When the circle is entirely inside the rectangle…

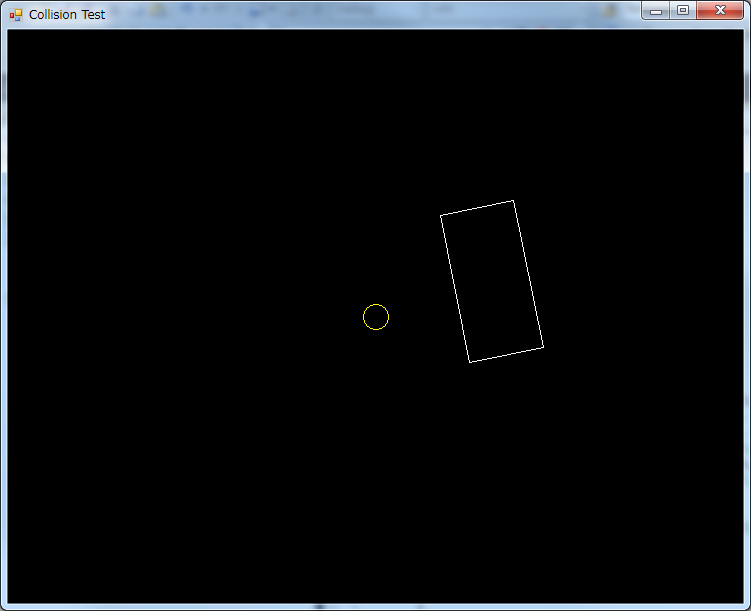

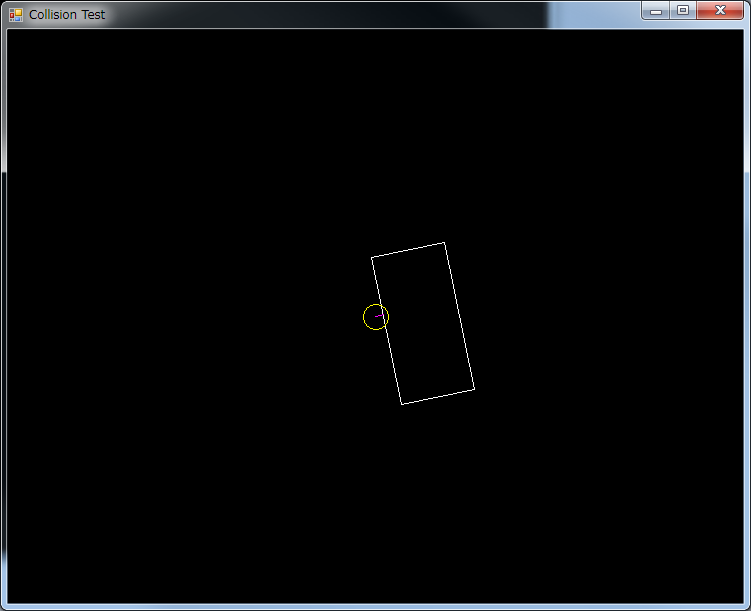

…And when the circle is partly inside the rectangle, that is, it is touching the border

These are two different types of collisions, and use different algorithms to determine whether or not there is a collision.

But first, let’s forget about the rectangle’s position and rotation. Our first approach will deal with a rectangle centered in the world, and not rotated:

Under these constraints, the circle is inside the rectangle when both the X coordinate of the circle is between the left and right borders, and the Y coordinate is between the top and bottom borders, like so:

public static bool IsCollision(CollisionCircle a, CollisionRectangle b)

{

// For now, we will suppose b.X==0, b.Y==0 and b.Rotation==0

float halfWidth = b.Width / 2.0f;

float halfHeight = b.Height / 2.0f;

if (a.X >= -halfWidth && a.X <= halfWidth && a.Y >= -halfHeight && a.Y <= halfHeight)

{

// Circle is inside the rectangle

return true;

}

return false; // We're not finished yet...

}

But this is not enough. This only works when the center of the circle is inside the rectangle. There are plenty of situations where the center of the circle is outside the rectangle, but the circle is still touching the rectangle.

In this case, we first find the point in the rectangle which is closest to the circle, and if the distance between this point and the center of the circle is smaller than the radius, then the circle is touching the border of the rectangle.

We find the closest point for the X and Y coordinates separately:

float closestX, closestY;

// Find the closest point in the X axis

if (a.X < -halfWidth) closestX = -halfWidth; else if (a.X > halfWidth)

closestX = halfWidth

else

closestX = a.X;

// Find the closest point in the Y axis

if (a.Y < -halfHeight) closestY = -halfHeight; else if (a.Y > halfHeight)

closestY = halfHeight;

else

closestY = a.Y;

And now we bring it all together:

public static bool IsCollision(CollisionCircle a, CollisionRectangle b)

{

// For now, we will suppose b.X==0, b.Y==0 and b.Rotation==0

float halfWidth = b.Width / 2.0f;

float halfHeight = b.Height / 2.0f;

if (a.X >= -halfWidth && a.X <= halfWidth && a.Y >= -halfHeight && a.Y <= halfHeight)

{

// Circle is inside the rectangle

return true;

}

float closestX, closestY;

// Find the closest point in the X axis

if (a.X < -halfWidth) closestX = -halfWidth; else if (a.X > halfWidth)

closestX = halfWidth

else

closestX = a.X;

// Find the closest point in the Y axis

if (a.Y < -halfHeight) closestY = -halfHeight; else if (a.Y > halfHeight)

closestY = halfHeight;

else

closestY = a.Y;

float deltaX = a.X - closestX;

float deltaY = a.Y - closestY;

float distanceSquared = deltaX * deltaX - deltaY * deltaY;

if (distanceSquared <= a.R * a.R)

return true;

return false;

}

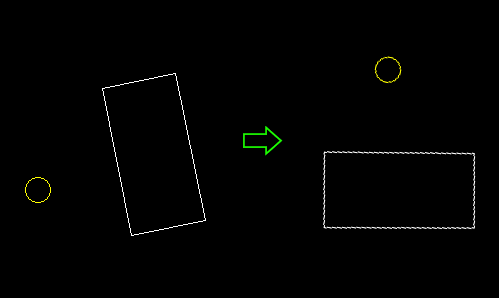

Looks good, but we’re still operating under the assumption that the rectangle is centered and not rotated.

To overcome this limitation, we can move the entire world -that is, both the rectangle and the circle-, so the rectangle ends centered and non-rotated:

In other words, we have to find the position of the circle, relative to the rectangle. This is pretty straightforward trigonometry:

float relativeX = a.X - b.X; float relativeY = a.Y - b.Y; float relativeDistance = (float)Math.Sqrt(relativeX * relativeX + relativeY * relativeY); float relativeAngle = (float)Math.Atan2(relativeY, relativeX); float newX = relativeDistance * (float)Math.Cos(relativeAngle - b.Rotation); float newY = relativeDistance * (float)Math.Sin(relativeAngle - b.Rotation);

And then put it all together:

public class CollisionRectangle

{

public float X { get; set; }

public float Y { get; set; }

public float Width { get; set; }

public float Height { get; set; }

public float Rotation { get; set; }

public CollisionRectangle(float x, float y, float width, float height, float rotation)

{

X = x;

Y = y;

Width = width;

Height = height;

Rotation = rotation

}

public static bool IsCollision(CollisionCircle a, CollisionRectangle b)

{

float relativeX = a.X - b.X;

float relativeY = a.Y - b.Y;

float relativeDistance = (float)Math.Sqrt(relativeX * relativeX + relativeY * relativeY);

float relativeAngle = (float)Math.Atan2(relativeY, relativeX);

float newX = relativeDistance * (float)Math.Cos(relativeAngle - b.Rotation);

float newY = relativeDistance * (float)Math.Sin(relativeAngle - b.Rotation);

float halfWidth = b.Width / 2.0f;

float halfHeight = b.Height / 2.0f;

if (newX >= -halfWidth && newX <= halfWidth && newY >= -halfHeight && newY <= halfHeight)

{

// Circle is inside the rectangle

return true;

}

float closestX, closestY;

// Find the closest point in the X axis

if (newX < -halfWidth) closestX = -halfWidth; else if (newX > halfWidth)

closestX = halfWidth

else

closestX = newX;

// Find the closest point in the Y axis

if (newY < -halfHeight) closestY = -halfHeight; else if (newY > halfHeight)

closestY = halfHeight;

else

closestY = newY;

float deltaX = newX - closestX;

float deltaY = newY - closestY;

float distanceSquared = deltaX * deltaX - deltaY * deltaY;

if (distanceSquared <= a.R * a.R)

return true;

return false;

}

}

public class CollisionRectangle

{

public float X { get; set; }

public float Y { get; set; }

public float Width { get; set; }

public float Height { get; set; }

public float Rotation { get; set; }

public CollisionRectangle(float x, float y, float width, float height, float rotation)

{

X = x;

Y = y;

Width = width;

Height = height;

Rotation = rotation

}

public static bool IsCollision(CollisionCircle a, CollisionRectangle b)

{

float relativeX = a.X - b.X;

float relativeY = a.Y - b.Y;

float relativeDistance = (float)Math.Sqrt(relativeX * relativeX + relativeY * relativeY);

float relativeAngle = (float)Math.Atan2(relativeY, relativeX);

float newX = relativeDistance * (float)Math.Cos(relativeAngle - b.Rotation);

float newY = relativeDistance * (float)Math.Sin(relativeAngle - b.Rotation);

float halfWidth = b.Width / 2.0f;

float halfHeight = b.Height / 2.0f;

if (newX >= -halfWidth && newX <= halfWidth && newY >= -halfHeight && newY <= halfHeight)

{

// Circle is inside the rectangle

return true;

}

float closestX, closestY;

// Find the closest point in the X axis

if (newX < -halfWidth) closestX = -halfWidth; else if (newX > halfWidth)

closestX = halfWidth

else

closestX = newX;

// Find the closest point in the Y axis

if (newY < -halfHeight) closestY = -halfHeight; else if (newY > halfHeight)

closestY = halfHeight;

else

closestY = newY;

float deltaX = newX - closestX;

float deltaY = newY - closestY;

float distanceSquared = deltaX * deltaX - deltaY * deltaY;

if (distanceSquared <= a.R * a.R)

return true;

return false;

}

}

In the next article, we’ll put some structure to all of this.